There are approximately 968 bridges within Upper Peninsula roads.

Of that number, 315 of those bridges are owned, operated and maintained by the Michigan Department of Transportation, while the remaining 653 are the responsibility of local entities, such as county road commissions, cities, townships and so on.

Motorists travel these bridges daily without giving it a thought. They exist for the purpose of getting us over rivers, lakes, valleys and many other landscapes to help us reach our destinations safely.

As with any other piece of critical infrastructure however, bridges can fail.

That’s a worst-case scenario, obviously, which is why MDOT performs routine inspections to prevent a failure from ever occurring.

According to MDOT, bridges are inspected at a minimum of every two years. Larger and more complex bridges, such as the Mackinac Bridge, are inspected more frequently. Bridges that are deemed to be in ‘poor’ condition may be inspected every six months, depending on the situation of the particular structure.

Every bridge in the state can be rated as ‘good,’ ‘fair’ or ‘poor’ condition upon completion of inspection.

Of the U.P.’s 968 bridges, 432 of them are in ‘fair’ condition, or 44.6% of the total. Approximately 417 bridges have ‘good’ condition ratings, or 43% of the total. Finally, 119 bridges are rated as ‘poor’ condition, or 12.2% of the total.

Should U.P. motorists be alarmed that there are more ‘fair’ bridges than ‘good’ ones? Not at all, according to MDOT Communications Representative Dan Weingarten and MDOT Bridge Engineer Jordy Maloney.

“They shouldn’t be concerned because if a bridge is dangerous, or could be potentially be viewed as a danger to the motoring public, we’re going to close it,” Weingarten said. “Because these guys are monitoring the bridges closely, the public can be confident that they’re driving over bridges that are safe to drive on.”

“I would add too that there’s checks in place,” Maloney continued. “It’s not like one guy goes out and makes his decision based on his own opinion, there’s multiple levels of review and check. There’s quality control checks, we review each other’s work, there’s other people that will hire consultants even to come in and review our work, so there’s a completely external source like an audit basically. And then the feds (federal government) themselves will pick random samples of bridges from what we’ve done and look at that. There’s multiple levels that add to that factor of safety that motorists should not be concerned about driving over a bridge. Our careers are on the line too if something happens.”

MDOT is responsible for inspecting and maintaining every bridge along the state trunkline, meaning any bridge along ‘I,’ ‘M’ or ‘U.S.’ routes. Local bridges must be inspected and maintained by the entity they fall under, but per federal regulations, MDOT is required to ensure those local entities are performing required bridge inspections regularly.

Roughly 93% of state trunkline bridges are rated in ‘good’ or ‘fair’ condition, while 7% are rated as ‘poor.’ Around 86% of local bridges are in ‘good’ or ‘fair’ condition, while 14% are rated as ‘poor.’

MDOT has 33 closed or posted bridges statewide, while the number of local closed or posted bridges sits at 1,106.

Local bridges are more often in worse conditions and have more posted weight restrictions than those of MDOT’s, primarily due to smaller budgets.

MDOT isn’t sugarcoating anything however, with Maloney admitting that bridge ratings continue to go down over time.

“In general, we’ve been trending downward on a condition rating as a state, as a region and the counties too,” he said. “It’s challenging sometimes to stretch those dollars any farther than we can because the bridges are deteriorating. We do everything we can with our maintenance to make sure that the bridges are safe and we protect them as best we can without having to invest millions and millions of dollars into replacing them, but at some point, a bridge will meet the end of its usable lifespan and unfortunately, a lot of them are coming to that at the same time, which makes it challenging to try and figure out how you prioritize one over the other when both are roughly in the same condition.”

Weingarten said MDOT generally hopes to get 75 to 100 years out of a single bridge, but each situation is different according to Maloney and fellow Bridge Engineer Pete Wessel.

“We have bridges that are 100 years old within the region that are still carrying traffic,” Wessel said.

“We do have some, like Pete was saying, they look great after 100 years old,” Maloney added. “And then we have some that are 30 years old that need a little more help. It’s all site-specific and it all depends on the individual bridge I guess. In general, we’re hoping to get at least 80 years out of a bridge when we build it which is a pretty long time.”

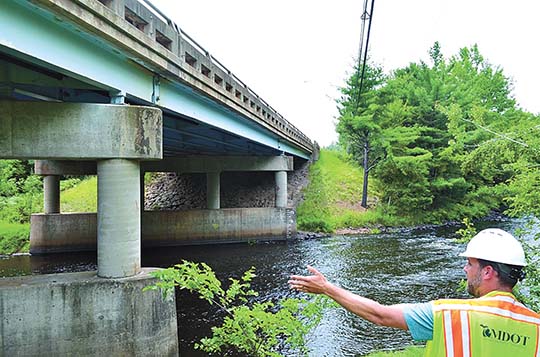

Wessel and Maloney were on the job Wednesday at the M-35 bridge over the Middle Branch of the Escanaba River in Gwinn to demonstrate the typical inspection process MDOT has in place. This three-span, steal beam pin and hanger bridge was constructed in 1967 and is currently rated in ‘fair’ condition as of June 17, 2019. The two-lane bridge averages 4,907 vehicles per day.

A bridge inspection typically begins from the top down, with crews first inspecting the deck, followed by the superstructure and substructure. The deck is the portion of the bridge that carries the traffic. The superstructure supports the deck and spans to different portions of the substructure, and the substructure supports the superstructure and distributes all bridge loads to below-ground bridge footings.

Inspection crews also look for things such as the condition of bridge approaches, slopes, drainage, waterway conditions, paint and more.

“Typically in our inspection process, we’ll look at all the stuff from up top,” Maloney said. “The deck, the approach slabs if it has it, we’ll look at the railings and the joints over the piers, and from there, we’ll go underneath and look at the superstructure, which is the beams or the girders, and then we’ll look at the paint on the beams, we’ll look at the bearings which support the beams. And then we’ll keep working our way down looking at the abutments and the piers and then from there, we’ll actually look at the stream bed itself to make sure that we don’t have any scour issues or stream degradation that could cause any instability in the structure as a whole because of the piers or abutments becoming unstable. That’s kind of a major concern of ours on some of these bridges because they do have certain types of footings that are susceptible to scour and instability. We have certain protocols in place during high flow events or heavy rains that we can monitor those and make sure that they do remain safe.”

MDOT also has two “Reach-All” machines that can be deployed throughout the state, making it easier for inspection crews to access hard-to-reach areas of the structure.

Bridges are rated on a scale of 1 to 9, with the deck, superstructure and substructure all receiving individual ratings. Anything from 1 to 4 is considered ‘poor’ condition, 5 to 6 ‘fair’ condition and 7 to 9 ‘good’ condition. This rating scale was created by the National Bridge Inventory, which is a database compiled by the Federal Highway Administration that keeps information on every bridge and tunnel across the country.

The ‘poor condition’ portion of the scale is further broken down into three subcategories, with 0 to 1 meaning the bridge has failed or failure is imminent, the bridge is closed and/or major rehabilitation or replacement is needed; 2 to 3 meaning the bridge is in ‘serious’ or ‘critical’ condition and that emergency repair or high priority major rehabilitation or replacement or temporary closure is necessary, and 4 meaning ‘poor’ condition and major rehabilitation or replacement is necessary.

‘Fair’ condition bridges mean preventative maintenance or minor rehabilitation tasks are required, and ‘good’ condition bridges mean routine maintenance is required.

Maloney reiterated that bridges rated ‘fair’ or ‘poor’ are no cause for concern from the public. MDOT will close or post a bridge if potential danger exists, and the chances of a collapse or failure unless extreme circumstances persist is almost zero.

“I hope nobody is concerned with the safety of the bridges we have here because we do use conservative estimates and things,” he said. “With our postings, we generally are pretty conservative. When there are issues, we have statewide experts look at the issues that we’re seeing and make sure that we are making the right choices, and we are spending the money where it’s needed to make sure all of the bridges are safe.

“One common misconception is, people see ‘poor’ rated bridges, and they think it’s unsafe, but that’s truly not what it means. It just means that it has deteriorated to a point where maybe we need to take some action, maybe we need to maintain it or put some more maintenance dollars into it to extend its lifespan. But it certainly isn’t a safety issue. If there becomes a safety issue with a bridge, that’s an immediate red flag where we either shut it down, post it, or do an immediate repair type-fix.”

“The regular inspections help ensure that nothing has changed beyond what we’re aware of,” Wessel added. “If it starts to deteriorate faster, then we’re increasing the frequency rate of the inspections and we’re out there every year instead of every two years.”

Maloney continued by saying bridges don’t typically deteriorate quickly.

“Fortunately, the one good thing that we have on our side is that bridges usually don’t deteriorate at a very high rate,” he said. “From one year to the next or every two years when we look at them, there’s generally not much change. So when we see something going, we generally have a five, six, eight, 10-year window where we can think, ‘Okay, well maybe we need to program a job and have a contractor come out and do some repair work on these.’ It gives us a little bit of time to usually make stuff happen when we need it to.”

MDOT estimates that $2 billion is needed to get all state-owned bridges up to ‘good’ or ‘fair’ condition, with another $1.5 billion to do the same for locally-owned bridges.

“The issues with maintaining bridges and finding the resources to maintain bridges is not just an MDOT problem, it extends across all of the local agencies as well,” Weingarten said. “We could all use more resources to help keep our bridges in better shape. These are big topics of discussion right now with infrastructure bills in Washington and in Lansing. Where do we get the money to do this? We are constantly looking for more resources to do the job of keeping bridges safer, and we’ll use those wisely if we get them.

“One idea that’s being proposed right now, Gov. (Gretchen) Whitmer has proposed a $300 million supplemental 2021 budget allotment for what’s called ‘bridge bundling,’ which is where MDOT would help local agencies bundle several bridge projects together under one contractor or a group of contractors so the work could all be performed at the same time. Hopefully saving money on design and economies of scale and things like that. If we got that $300 million, local agencies might be able to do like 130 bridges, and those would be some of the ones that are in the most critical condition or are in some cases, closed.

“We know that if we get more resources, we can keep the bridge ratings in the state of Michigan higher.”

How can you find out what condition a bridge is in? All of that information is available to the public via MDOT’s Bridge Conditions Dashboard, a fairly new tool released in 2019 that provides the public data such as amount of bridges in an area, what condition each structure is in, total deck area and much more.

“The Bridge Condition Dashboard that’s available to the public, you can zoom in on this (M-35 bridge) structure or any other bridge in the state and get a whole wealth of information,” Weingarten said. “The last time it was inspected, what it’s current ratings are … you can also look at different areas. If you want to see how a particular county or city is doing, you can zoom in on the map. Each structure is color-coded, so you can see right away if it’s in good, fair or poor condition. There’s a wealth of information out there that the public can have access to at any time. It’s not up-to-date right to today, but it’s as current as we can possibly make it, and it’s the same data that (bridge engineers) gather and report to the federal government.”

To view the Bridge Conditions Dashboard, visit www.bit.ly/36B9vi1.

To learn more about the Michigan Department of Transportation, visit www.Michigan.gov/ MDOT.

This article appeared in The Daily Mining Gazette. For more, click here.