The Michigan State Transportation Commission approved a plan Thursday to borrow up to $3.5 billion over the next four years to inject a rush of money into the state’s crumbling road system.

Under the plan, unveiled by Gov. Gretchen Whitmer on Wednesday night, the state will sell bonds and take on debt that will be paid back over the next 25 years. The bond proposal will nearly double the Michigan Department of Transportation’s five-year plan for road and bridge projects focused on the state’s major highways.

But the improvements will be focused solely on the state trunk lines — interstate freeways or major state arteries. None of the money will flow to county road commissions or local governments for road repairs.

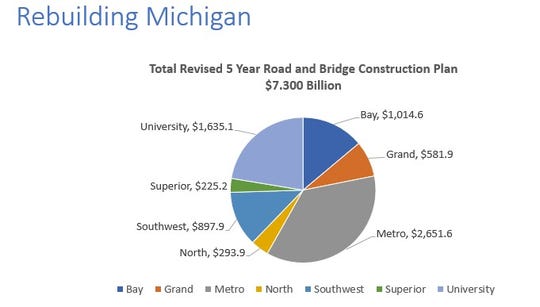

The Department of Transportation’s past five-year plan was $3.8 billion. With the money from the bonds, the new five-year plan will be $7.3 billion and include 49 new projects, which are mostly rebuilds of roadways. There are another 73 accelerated projects that would replace structures or rehabilitate roads.

Metro Detroit’s three counties would get 28 new or accelerated projects.

“This plan pulls a number of projects forward so it will cut down on the cost of inflation and help us locking in favorable rates now,” Whitmer told reporters Thursday at a roundtable.

The projected cost of the $3.5 billion program would be about $5.2 billion assuming consistent annual debt service payments of $206.6 million for 25 years, according to the Department of Transportation. Since inflation over the time period would increase the price tag, the discounted “present value” of Rebuilding Michigan would be $3.6 billion, said MDOT spokesman Jeff Cranson.

“Leaving bridges and roads to crumble and turn to gravel is imposing its own debt burden on further generations,” Cranson said.

Republican legislative leaders expressed concerns Thursday that Whitmer’s description of the bonding plan Wednesday made it sound like a long-term funding solution, not a short-term financing tool.

Whitmer did note during her address that she and the Legislature still would need to seek a long-term solution, but GOP leaders argued the overall impression she left was that of a long-term fix through road loans.

“I’m concerned that we’ve now got people convinced that she’s magically found money that can take care of roads and that’s not the case at all,” Senate Majority Leader Mike Shirkey told reporters Thursday. “In fact, as I said a moment ago, that will exacerbate the problem down the road.”

The bond program will eventually increase the state’s annual debt service payments for State Trunkline Fund bonds from about $118 million in 2020 to somewhere near $300 million, Michigan Department of Transportation Director Paul Ajegba said after the meeting.

Whitmer said she anticipated about $200 million a year in added debt service payments because Michigan’s “debt load is falling off” — an amount that she said “has been essentially what we have committed over the last number of years. It won’t be a dramatic increase.”

Michigan’s roads and bridges have been projected to require more than $2 billion a year in extra money to improve their condition. The new infusion would add an average of $700 million a year over MDOT’s five-year plan.

The bond program is a smart and cost-effective way to address “a looming crisis,” said commissioner George Heartwell, an independent and former mayor of Grand Rapids.

“We still need an increased dedicated source of revenue from the Legislature to solve the long-term, going forward problem,” Heartwell said during the meeting. “This will put us back on track to fix our Michigan roads.”

There is a 25% annual future cost savings to rebuilding pavement as opposed to simply rehabilitating the same road, added Chris Yatooma, a Republican appointee on the Transportation Commission.

What roads get targeted

In the new $7.3 billion five-year plan, the department’s Metro region — Macomb, Oakland and Wayne counties — will get projects worth $2.6 billion or about 35% of the funding. There are six other regions in the state.

Without the bond program, the state would have been able to only patch potholes on that portion of highway, MDOT’s Ajegba said.

Macomb County would get two new projects starting in 2021. In a $60 million effort, Interstate 94 would be rebuilt from 8 Mile to 11 Mile, while M-59 would get an overhaul from Romeo Plank east to I-94 costing $66 million.

The project list includes investing $324 million into rebuilding portions of I-275 in Wayne County. Another $217 million would be spent starting in 2021 to overhaul Interstate 96 in Oakland County from Kent Lake Road to Novi Road.

Metro Detroit is expected to get 18 of the 73 accelerated projects. They would cost about $267 million or 28% of the $954 million in total sped-up projects.

The region’s three counties will get at least one large accelerated project starting next year.

The largest at $55.4 million is in Macomb County, where M-53 will get rehabilitated from 18 Mile to 27 Mile.

In Oakland County, M-59 will be rehabbed from Milford Road to Pontiac Lake Road for $52 million.

In Wayne County, 8 Mile or M-102 will get rehabilitated from Woodward Avenue east to Van Dyke for $44 million.

Battle over costs

The average term of the bonds will be “approximately 25 years,” said Laura Mester, chief administrative officer for the Department of Transportation. The department is expecting to pay interest rates from 2.5% to 3.5%, Mester said.

“This is akin to taking out a mortgage to build a new roof,” Whitmer said. “Sometimes for long-term investments the wisest thing to do is lock in a low interest rate and actually fix the problem.”

The governor unveiled her plan to pursue $3.5 billion in bonds for Michigan’s infrastructure during her Wednesday night State of the State address. She described the proposal as “Plan B” after the Legislature rejected her 2019 proposal to increase the state’s 26.3-cents-a-gallon gas tax by 45 cents.

“So, from now on, when you see orange barrels on a state road: Slow down, and know that it’s this administration fixing the damn roads,” Whitmer said during her speech.

At the Thursday roundtable, the Democratic governor said the road bonding plan still means “the Legislature has got to come to the table with a funding solution.”

Shirkey, R-Clarklake, and Speaker Lee Chatfield, R-Levering, maintained that they had presented various long-term funding options to the governor in 2019, including a plan that would ensure every tax penny paid at the pump went toward roads — with no diversion to the School Aid fund — and teacher pension refinancing that would free up as much as an estimated $1 billion that could be used to hold the School Aid Fund harmless.

Chatfield has been pushing to free up the 6% sales tax on fuel so it could go exclusively to road repairs instead of aid for schools and local communities.

Whitmer’s version of negotiations in 2019 is “revisionist history,” he said.

“Don’t forget this governor vetoed nearly $400 million in one-time funding for roads,” Chatfield said. “Why? Because she said it wasn’t a long-term road funding solution and that she wouldn’t sign something unless it was a long-term plan.

“So what’s her Plan B? A short-term financing plan.”

Former Govs. John Engler, a Republican, and Jennifer Granholm, a Democrat, used their administrative powers to authorize the sale of bonds to fund road improvements.

The state can issue new bonds against State Trunkline Fund revenues, mainly registration fees and gasoline taxes, and projects are expected to focus on state highways.

Ajegba said the state still needs a long-term funding solution for its infrastructure that improves local roads.

“This is just to prevent us from falling off the cliff,” he said.

The state’s outstanding debt against State Trunkline Fund revenue and anticipated federal aid previously peaked at about $2.3 billion in Fiscal Year 2009, according to the House Fiscal Agency. It was down to $1.2 billion by 2018.

This article appeared in the Detroit News. Read more here.