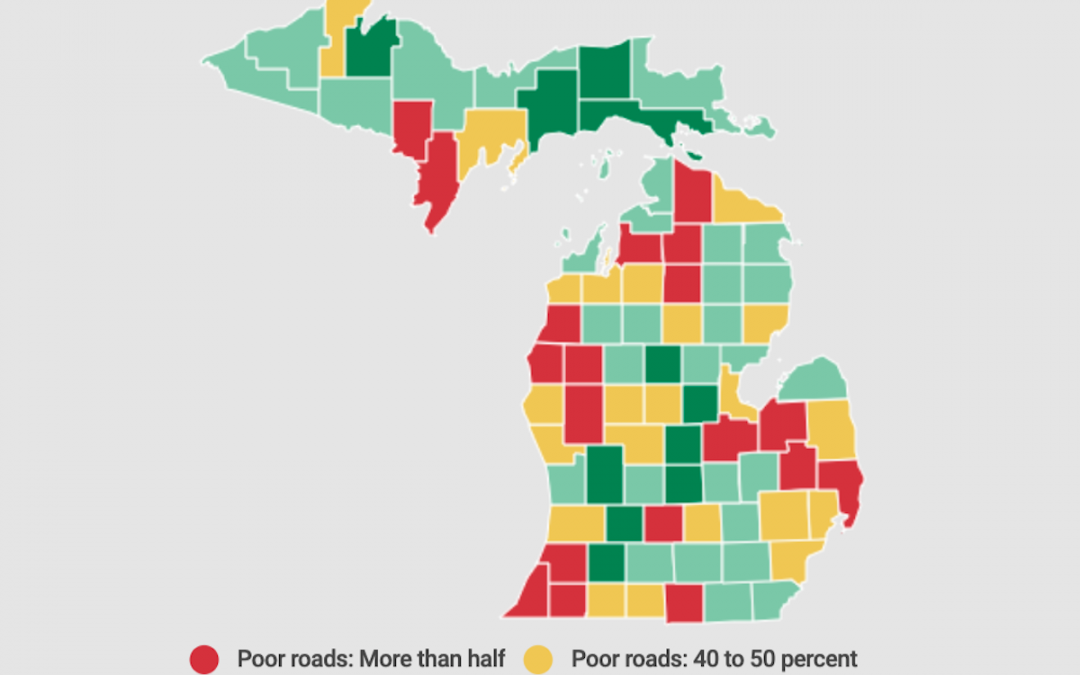

No doubt, Michigan’s roads are bad. But their degree of awfulness varies widely throughout the state, rankings show, and that could inform debate about whether a tax increase is necessary for repairs.

Republican legislators this week approved budgets that include $400 million in road and bridge spending, ignoring Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s call for nearly $2 billion in spending through a 45-cent gas tax increase.

A roads deal could come yet this fall, however, after the start of the Oct. 1 fiscal year. The urgency is caused in part because road conditions have deteriorated over the years and the percent rated “poor” has increased from 30 percent in 2008 to 41 percent last year, according to ratings from state and local officials and compiled by the Michigan Department of Transportation.

But those ratings aren’t uniform – in counties both urban (Kent) and rural (Schoolcraft), roads get passing grades. While in other urban counties (Saginaw, Oakland) and rural ones (Manistee, Cheboygan), poor roads outnumber the good and fair roads combined.

“You will find pockets where people think it’s not as bad as it is,” said John Sellek, a public affairs consultant who long worked for former Attorney General Bill Schuette, a Republican who lost to Whitmer for governor last fall.

In some counties, Sellek noted, road conditions have been managed well.

Look no further than Barry and Eaton counties in west central Michigan. They share a border and both are mostly rural. Barry has the best rated roads in the state while Eaton has the second worst.

“It’s a source of great pride for the road commission,” said Jake Welch, operations director for Barry County. A dozen times a year, he said, residents thank the commission for their work, noting the county’s roads are better than their eastern neighbor. “I definitely notice it too,” Welch said.

Running for governor, Whitmer campaigned hard on fixing infrastructure, making “fix the damn roads” her mantra. But since her victory, her prescription for solving the problem with the largest gas tax in the nation has been rejected by Republicans and Democrats alike.

Sellek said most everyone agrees the roads are bad – but do not trust that a big tax increase will solve the enormity of the problem.

Republicans have acknowledged the roads need for more money but finding a palatable increase has proven difficult. Senate Majority Leader Mike Shirkey, R-Clarklake, has suggested the state has too many paved roads. In his county, Jackson, the percent of roads rated “poor” has nearly tripled in a decade to 33 percent, but that’s still below the state average.

Other GOP leaders live in counties with better roads too: House Speaker Lee Chatfield, R-Levering, lives in Emmet County, where just over a third of roads are poor, again below the 41 percent statewide. And from 2008 to 2018, the percent of county roads rated “good” jumped from 16 percent to 29 percent.

(In Wayne and Oakland counties, the state’s most populous and the home of many of the state’s Democratic legislators, road conditions are worse than the state average.)

One solution: local funding

Welch said Barry County has only gotten by because local communities, including the 16 townships in the county, have pitched in to increase road funding. Five townships have special road taxes and the others dipped into general tax funds, he said.

As state funding stood nearly stagnant for almost 20 years, from 1997 until the 2015 roads deal that raised the gas tax, road maintenance costs rose markedly, Welch said. Without the townships pitching in “we would have been in big trouble,” he said.

The townships contribute roughly $1.5 million, or 15 to 20 percent of the road commission’s budget, Welch said.

Statewide, not all townships, cities and villages have dedicated road taxes. Statewide, 32 have dedicated property taxes for roads, fewer than half of the state’s 83 counties.

Trying to find a simple reason why Barry is better than Eaton is hard. Eaton County has a roads tax yet 66 percent of roads in the county were rated “poor”. Barry does not have a countywide millage and only 13 percent got a poor rating; 40 percent were rated “good”.

Welch’s counterpart in Eaton County, Blair Ballou, said he’s envious of his neighboring county’s help from townships. He said that’s one reason Barry County has better roads.

But Eaton County voters narrowly approved a road tax in 2014 and Ballou said the money, about $4 million a year, along with increased state funding from the 2015 roads deal, is allowing the county to repair and replace many more miles of road.

“Now that we have the millage it’s really getting things done,” he said.

Bad for you, good for some

In Dickinson County in the Upper Peninsula, drivers may hate the poor roads (12th worst – 54 percent rated “poor”), but it works out for for B&B Tire in Ironwood, on the far western edge of the Upper Peninsula.

Every spring, during the thaw from the long U.P. winter, the shop is filled with customers spending money on new tires and alignments.

“The bad roads are good for our business,” said Kevin Barglind, manager of the shop, “but I have people (coming) in here all the time complaining. Nobody understands why they’re so bad.”

While politicians in Lansing argue over finding the money, be it $400 million (the GOP leaders) or $1.9 billion (Whitmer), the figures are smaller – and easier to understand: the cost of a new set of tires or the price of an alignment, but the solution is just as evasive as it is 500 miles south in Michigan’s capital.

“People don’t know who to blame,” Barglind said. “They just know they (the roads) are bad and they don’t know how to fix them.”

Dickinson County abuts Wisconsin in the far western edge of the Upper Peninsula and the difference offers a stark contrast to Barglind. “We’re two miles from the Wisconsin border,” Barglind said. “I don’t know what their tax (rate) is, but their roads are far superior to ours.”

According to MDOT, Wisconsin spends double, annually, on road funding: $302 per person compared to $154 per person in Michigan.

City roads vary too

When it comes to the roads in the state’s cities and villages, the disparity is wide. In Inkster, a poor community in Wayne County, more than 80 percent of the city’s 70 miles of roads are rated poor. Yet a few miles away in Woodhaven, it’s 38 percent – and 48 percent are considered in good condition.

So, too, is that wide gap found in Oakland County: Wixom has some of the worst roads (76 percent poor) while Rochester Hills has more good roads than fair or poor.

Oddly, the city of Lapeer has the best rated roads – 54 percent rated “good” – yet the county as a whole has some of the worst, overall with 63 percent rated “poor.”

Read more at https://www.bridgemi.com/michigan-government/hate-michigan-roads-your-neighbors-may-be-way-better-database.