The daily commute for Amanda Miles used to be so simple.

Six or seven minutes to work as a bartender. Another short trip for her kids to elementary school, just around the corner from her job.

That all ended two years ago when the county shut down the decaying Waltz Road Bridge that leads into the small Wayne County community of New Boston. The bridge was one of three immediately closed after a countywide inspection in 2017.

“There were some gaping holes on the sides of the bridge,” said Beverly Watts, Wayne County public works director.

Added County Commissioner Al Haidous: “The hole through the steel and the cement — I could’ve fell through it.”

Since that closure, if the trains were clogging up the alternate route, Miles’ commute to her job at McNasty’s Saloon could triple. Same hassle for her kids, who spent up to 90 minutes sometimes on the school bus to Miller Elementary.

For Miles and her family, the bad bridge has been an inconvenience. For local New Boston businesses, it’s been a stranglehold.

“My kids ask me all of the time, ‘When’s the bridge going to be open, when is the bridge going to be open?’ ” Miles, 35, said recently. “This is our downtown area, you know, we’re a really close, tight-knit, tiny community and for the main vein of our town to be closed has just really crippled it.”

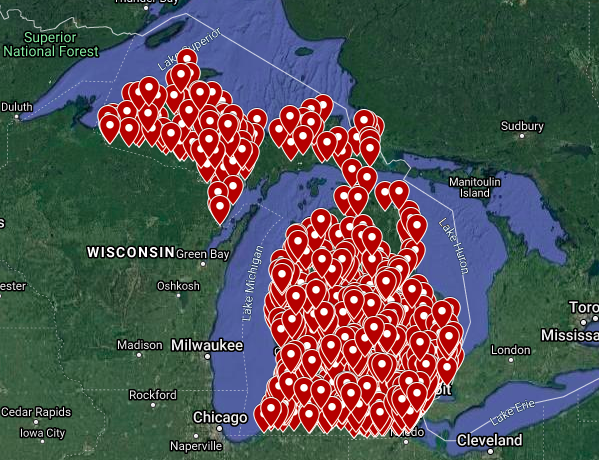

For scores of people around Michigan, where more than one in 10 bridges are in poor or worse condition, there isn’t much good news.

For some, there’s no fix in sight for their local bad bridges. Communities in Michigan just don’t have nearly enough money. As Gov. Gretchen Whitmer and the state Legislature grapple over a problem everyone recognizes — that the poor condition of Michigan’s roads and bridges is reaching a crisis point — there is not yet any help on the horizon, though the governor did say at the Mackinac Policy Conference recently that she wants transportation funding to be the next big issue for the Legislature.

For places like New Boston, a Huron Township community that is only now emerging from two years without a working bridge, this reality is unacceptable.

“This isn’t a luxury, it’s a necessity,” David Glaab, township supervisor, said of the Waltz Road Bridge. “This is just an absolute necessity. There are no really plan B’s or alternative routes.”

Source: The Detroit Free Press

Wayne County owns the most

Local communities own 59% of Michigan’s 11,000-plus bridges that are longer than 20 feet. Many local agencies are struggling to keep up with the costs of maintaining and replacing them. The data from 2018 tells the story —14% of locally owned bridges were in poor condition compared with just 5% of those under state control. The percentage of poor bridges is expected to rise in the coming years if lawmakers don’t come up with more money to fix them.

Some of the largest bridge owners are counties. Macomb, Saginaw, St. Clair, Tuscola and Wayne counties each have more than 200 bridges with spans greater than 20 feet. Of those five, Tuscola at 5% had the lowest rate of bridges in poor condition, while Wayne County had the highest at 30%, according to a Free Press analysis of 2018-19 bridge ratings and replacement cost data.

The sheer number of these structures puts the estimated replacement cost for Wayne County’s bad bridges at roughly $406 million, the highest among local bridge owners statewide, according to a Free Press analysis of Michigan Department of Transportation data. From its meager allotment of state transportation funding, Wayne sets aside just $10 million a year for its bridges.

In Wayne, the Detroit River island community of Grosse Ile requires that drivers cross a privately owned toll bridge or the county-owned “free” bridge. Grosse Ile is home to a dozen bridges owned by Wayne County, and eight of them are in poor or worse condition, including a bridge that is closed. Five of the poor bridges have weight restrictions and one bridge, the Grosse Ile Parkway bridge over West River Road, has temporary supports to allow traffic to access the free bridge crossing the Trenton Channel, a bridge that is also in poor condition.

Bill Heil, 77, a longtime resident of the sparsely populated island, says he wants the roads and bridges fixed. But, he says, he is acutely aware of how population and traffic play into a government’s repair plans.

“We’re like the red-headed stepchild that way,” Heil said recently. “When you’re running a county, when you’re running any government, you want to use your resources, which are always limited, to bring the most benefit to the most people.”

There is no shortage of other bridges in poor condition in Wayne County, the most populous county in the state with the greatest number of spans more than 20 feet long.

“We have over 300 bridges in Wayne County and I gotta tell you our budget for maintaining and repairing them is minuscule,” said County Executive Warren Evans.

In a recent report, Wayne County outlined 11 bridges with replacement costs of $10 million or more each because of their size, structure or complexity. Only one is rated in good condition.

One of those bridges is the Grosse Ile Parkway bridge that crosses the Trenton Channel, the only non-toll bridge that connects to the community. It is scheduled for reconstruction in two phases starting in the fall and is currently weight-restricted to vehicles weighing 26 tons or less. A loaded garbage truck weighs about 25 tons.

Local bridge gap

With no new ideas coming to fruition from Michigan’s government — the Republican-controlled Legislature has scoffed at the Democratic governor’s proposal to raise the gas tax by 45 cents — the main source of funding for local bridges are state dollars from the Michigan Transportation Fund. The fund, created by Public Act 51, is revenue raised primarily from motor fuel taxes and vehicle registration fees.

Just like the state, a majority of local governments spend this money on roads, not bridges.

In fiscal year 2017, county road commissions in total received $900 million from Act 51 and spent a paltry $42 million of it on bridges, according to the Transportation Asset Management Council, a legislative body made up of transportation officials. The share to cities and villages was about $450 million and just $15 million went to bridges.

Local bridge owners also apply for funding to the state’s Local Bridge Program. Although the program is limited by the approximately $50 million a year statewide that is divvied up by region.

The gap between available funds and what is actually needed is clear.

In Macomb County, about 12% of county-owned bridges were in poor condition and the estimated replacement cost for these 25 bridges was $47 million last year. The costs are limited to the physical parts of the bridge and do not include a long list of items also necessary, such as engineering and design, demolition and lighting.

County officials told the Free Press they spend about $1.5 million annually on bridges. This year, they submitted the maximum number of bridges to the local bridge fund for possible funding. But within that limited budget, few are chosen.

Oakland County owns a higher percentage of structures in poor condition — 23%. The projected cost to replace these 26 poor bridges was $23 million in 2018. Over the last five years, the county has spent an average of about $4.2 million per year.

Washtenaw County owns 119 bridges and culverts that require inspection; 22% were in poor condition in 2018 and it’s estimated to cost $29 million to replace them. This year, county officials plan on spending just over $1 million on bridges, which includes match contributions required to receive federal/state grants, contract services and other expenses, said Emily Kizer, communications manager at the Washtenaw County Road Commission. Washtenaw will spend more than that on additional culvert and drainage improvements.

Weather can be tough on the budget

In May, a culvert failed under Braun Road in Washtenaw County. The 3-foot diameter pipe was washed away in heavy rains. The culvert’s diameter is not long enough to require inspection.

“People drive over these things every day and have no idea that they are there,” Kizer said.

Braun Road is a local road so the county road commission is partnering financially with Saline Township to replace it with a 6-foot diameter pipe this summer. “The Braun Road one is kind of an exception to when we have bridge failures on local roads. It is not always the case that we can get it funded so quickly,” Kizer said. In fact, she said, another recent culvert failure led to the closure of Lehman Road in Sharon Township. The road will be closed until further notice, she said.

Tuscola County in the Thumb area saw more than 30 culverts wash out after heavy rains over Memorial Day weekend.

The cost to fix all of the structures from the holiday rainfall? “Our rough estimate right now is about $4.5 million,” said John Laurie, chairman of the county road commission. That’s about 20% of their current budget. “That’s what Mother Nature can do in a few hours,” he said.

Overall, Tuscola County takes good care of its bridges, with only 5% in poor or worse condition. Laurie credits the generosity of the residents for the bridge conditions.

They have provided two countywide millages that date back decades: 1 mill for primary roads and a half a mill for bridges. That generates about $1.2 million for roads and around $600,000 for bridges, according to Laurie. In addition, there are 23 townships in Tuscola County, 17 of those townships have their own road millage — usually a mill or two.

The county spent nearly $3 million on bridges in 2017.

“I gotta give the people of this county credit, they’ve done a really good job in funding, maintaining the infrastructure,” Laurie said.

What about cities and villages?

Every county in Michigan owns a bridge, but not every city or village is a bridge owner. And bridges are a definitely a costly piece of road.

Cities like Ferrysburg on the west side of the state and Mount Clemens have only one bridge in poor or worse condition, but the costs to replace a bridge for communities all over Michigan can be staggering.

“Many times, a bridge reconstruction is their entire capital budget for the year and so they can either do several smaller things to go spread it around their community or they can fix one bridge,” said Trevor Brydon, transportation planner at Southeast Michigan Council of Governments. “It is a pretty stark trade-off that they face when trying to repair bridges.”

Ferrysburg, with its 3,000 residents just north of Grand Haven, owns two bridges. The West Spring Lake Road Bridge, also known as Smith’s Bridge, is in bad shape, and it connects two residential areas.

City Manager Craig Bessinger said Ferrysburg has applied three years straight without success for funding to the Local Bridge Program. The city has also tried and failed to pass a millage. The bridge is estimated to cost $12 million to replace. The city received $300,000 in 2017 from the Michigan Transportation Fund. Without additional funding, Bessinger says the city has been forced to reduce the weight further and prohibit truck traffic. He said Thursday that on June 17 the City Council is expected to discuss closing the bridge to vehicles.

In Mount Clemens, the Crocker Boulevard bridge over the Clinton River is in serious condition. Jeffrey Wood, Mount Clemens assistant city manager, said the city has applied to the Local Bridge Program with the assistance of an outside engineering firm multiple times, with no success. Without additional funding, eventually alternate routes may have to be planned, he said.

In Bay City, where the Saginaw River runs through the heart of the community — four bridges connect people to either side of town. Two are owned by the state and two are owned by the city. Both of the city-owned bridges, Liberty and Independence, are in fair condition, but they both have erosion around their foundations, which requires monitoring.

The city has put out a request for bids to form a public-private partnership that could raise money for both bridges by charging tolls.

“We’re trying to get grants… our staff has been working diligently on finding other sources of revenue that would apply to the bridges, so far to no avail,” Mayor Kathleen Newsham said.

Back in New Boston

Since the Waltz Road Bridge was closed, New Boston’s downtown area has suffered.

The ice cream shop and the pizza place closed. McNasty’s suffered a precipitous drop in its business.

Chad Frazier, whose grandparents bought the saloon in 1977, said the bridge closure was a surprise.

“We kind of woke up … and we had the sign next to the building and that was it,” Frazier said.

He said the situation cut business at his place, which features a great burger, by 30% to 40%.

“There’s a lot of people that live on the other side of the bridge that can’t get here,” he said in May. “It’s put a big wrench in the whole community.”

Barbara Gibbs, 86, the former owner of Gibbs Sweet Station in downtown New Boston, said the closure was terrible for business.

“I did close early last summer because I wasn’t getting the business and I just figured why should I stay here and sit when nobody’s coming in?” Gibbs said.

She had been in the ice cream business for roughly 35 years before she sold her shop, which was adorned with antique ice cream memorabilia. She’s now retiring and moving out of state.

“I was very proud of my store … nobody, not even Disney World had an ice cream shop like I had,” she said.

But there’s better news. On Monday, under a shower of fireworks and a priest’s blessing, the Waltz Road Bridge reopened and traffic is flowing through New Boston again. The village, unlike so many other places around the state, has a new beginning.

At the ribbon-cutting ceremony, Evans, the county executive, made clear the need for more money.

“I am not here to make a political discussion. I am just here to say that with the number of bridges we have and the number of roads that need repaired, we have very little money to do it,” Evans said. “A famous saying that a friend of mine told me a long time ago, ‘It is very, very difficult to make chicken pie out of chicken feathers.’ And in terms of dollars, that’s what we’re currently working with. We’re doing what we can but at some point, we’ve gotta pay the piper and do more for road repairs and do more for bridge safety and bridge repairs.”

The Waltz Road Bridge cost the county $2.5 million to replace. The county has nine more closed bridges on its books and dozens more in bad shape.

With the amount of dollars dedicated to bridges falling far short, it is not clear how Wayne County, like so many other Michigan communities, is going to close the gap.

This story has been updated to properly identify the river that the Crocker Blvd. bridge crosses in Mount Clemens.

This article appeared in The Detroit Free Press. Read more here.